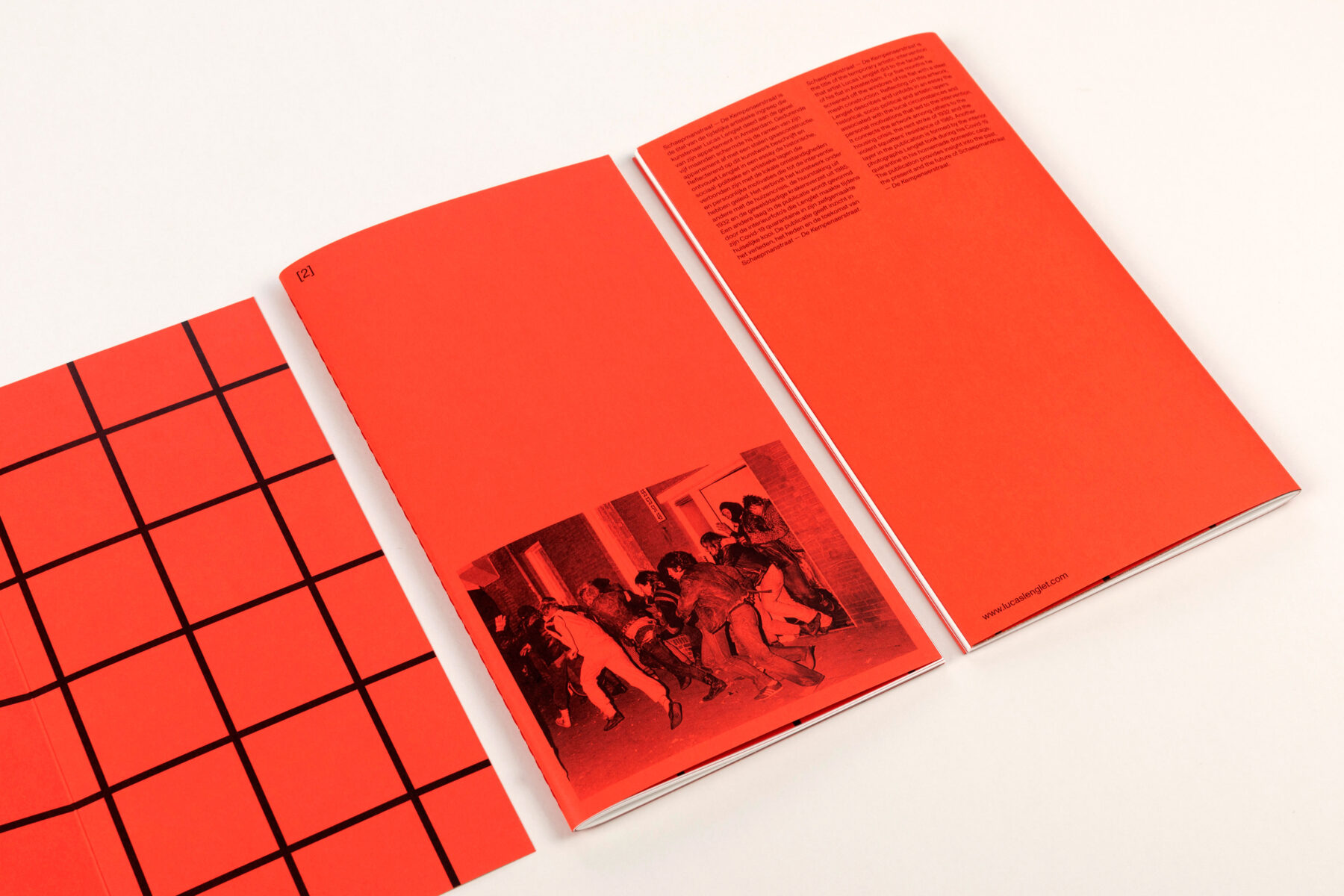

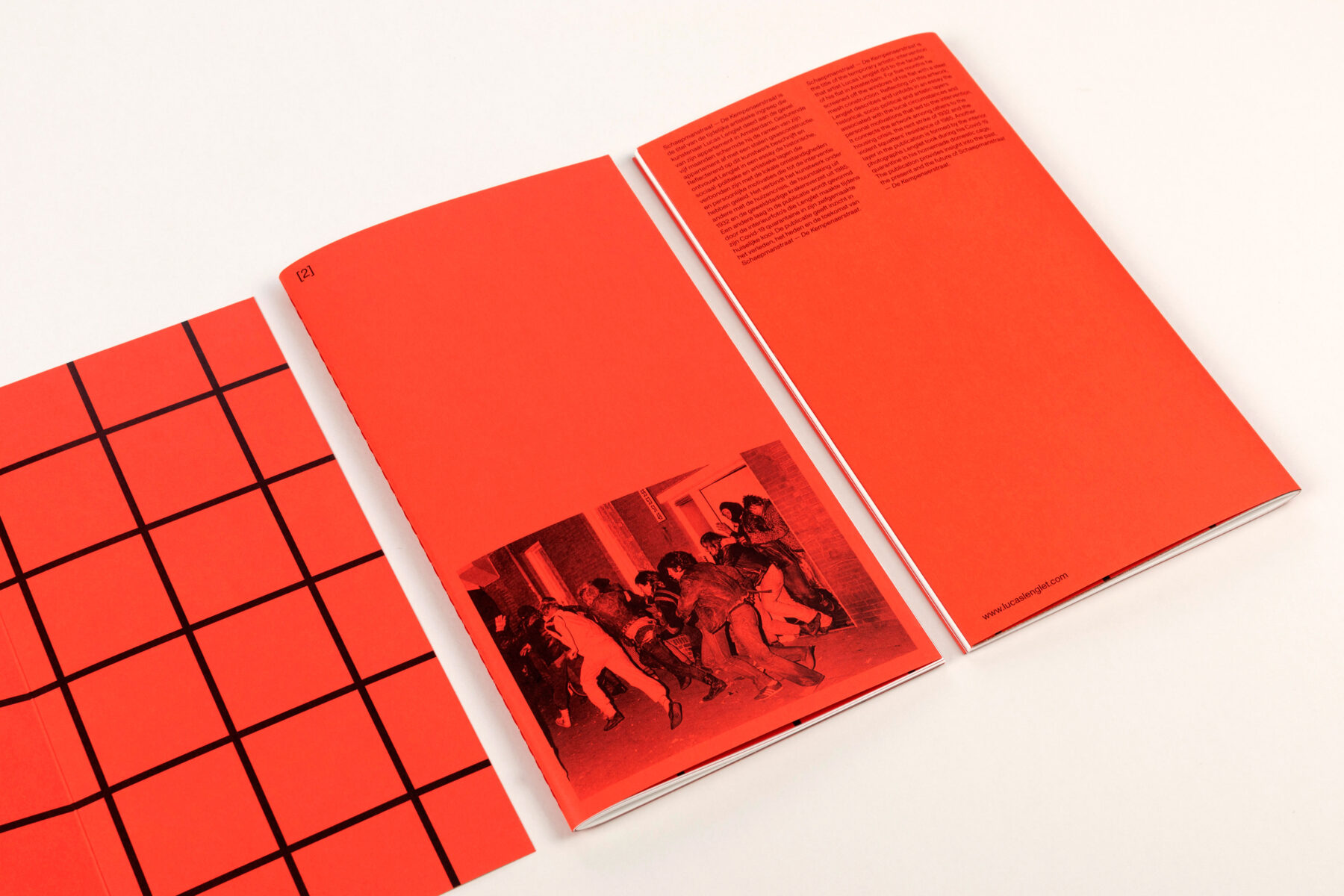

publication Schaepmanstraat – De Kempenaerstraat

2023

160 x 280 mm

80 p., oplage 100

Dutch – English

design Michaël Snitker

photo’s by thebookphotographer.com

snitker.com

welcomestranger.com

2023

160 x 280 mm

80 p., oplage 100

Dutch – English

design Michaël Snitker

photo’s by thebookphotographer.com

snitker.com

welcomestranger.com

Schaepmanstraat – De Kempenaerstraat is the title of an artwork that Lucas Lenglet made for the facade of his home in Amsterdam at the invitation of Welcome Stranger Foundation. He placed panels of red steel mesh on all the windows of his corner apartment for a period of five months. Visible from the street, the work turned his home into a cage. When Covid forced the artist into quarantine, he suddenly found himself living in a self-built cage for weeks. This situation prompted him to write the following text in which he describes the historical, socio-political and artistic layers of this work in relation to his motives and personal circumstances.

Inclusion and exclusion

On the project Schaepmanstraat – De Kempenaerstraat

23 October 2020 – 29 January 2021

By Lucas Lenglet

When I was born my parents lived in a rented flat. Then we moved to a terraced house, from there to another terraced house, and after that to a detached house where I spent my teenage years. After I left my parental home to go and study, I lived in rented rooms, (shared) apartments, old school buildings, factories and social rental accommodation. At one time or another they were all ‘home’ to me, so much so that I always took suitable housing for granted.

When I separated from my partner, I expected to enjoy a measure of independence, but, paradoxically in fact, I became very dependent on others – especially when it came to housing. The private housing market with its sky-high rents was out of my league, and buying a house was way beyond my reach. So I had to rely on social rental housing with its online system based on calculated odds, waiting lists, inadequate documentation and poorly informed staff during infrequent house inspections.

My confrontation with the prevailing housing shortage shocked me enormously. Few homes were available, and those that were turned out to be unsuitable for a parent and child, or were too far from either his school or my studio to guarantee continuity. Apparently, the stifling reality of not having a roof over my head didn’t make me a priority.

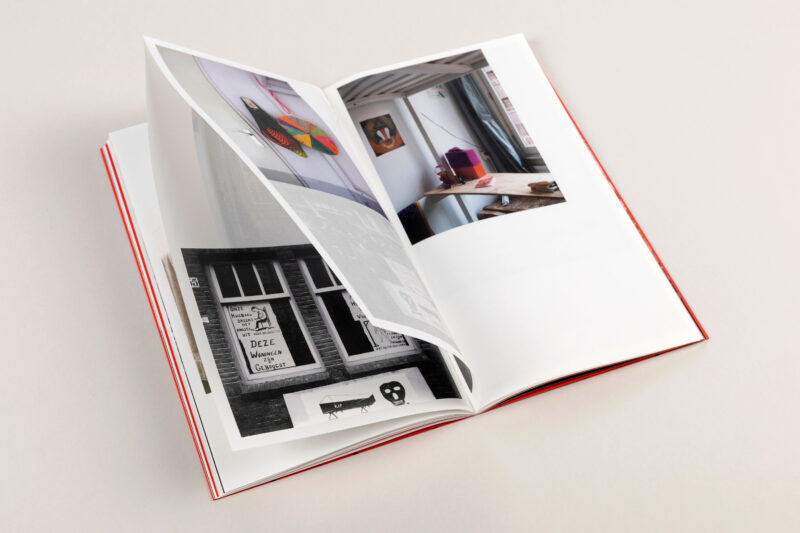

Besides the acute housing shortage, I had the impression, when looking for a home, that what was on offer were not actual homes but rather the concept of a home. Walls, floors and ceilings, spaces for cooking, washing, sleeping and living – they were all there but stripped of most qualities.

For a wall does more than provide protection from the elements and outside threats; it should also ensure privacy, keep out sound, hold a nail hammered into it, give the room a colour. Hardly any of that was possible in the homes I visited.

This applies to all the primary functions of homes. They should exist not only by virtue of the facilities they contain but certainly also because they have been made with love and respect for those living in them. Loveless and cheaply built rental spaces serve nobody’s interests but those who own them. What I encountered was a simulation of living space, the concept of living space, but not space in which to actually live.

Society’s acceptance of this inequality, despite the knowledge that the basic need for housing and living space is the same for everybody, bewilders me. Under the motto ‘beggars can’t be choosers’, a vast group of people have to settle for what they are offered and they have almost no control of or say in their housing situation. But why should anybody be a beggar in a country like the Netherlands? Is money the only reason why somebody can or cannot participate in society? Or should human existence itself be enough to enjoy equal rights and opportunities?

After searching for half a year I did eventually find a home. But during my six months without one I began to think differently about the meaning of home. Especially when I sensed that the larger construct that was once considered to be a home – I mean the city, its inhabitants and their accompanying culture – had turned its back on me and made it clear that I was not an natural and indispensable member of it.

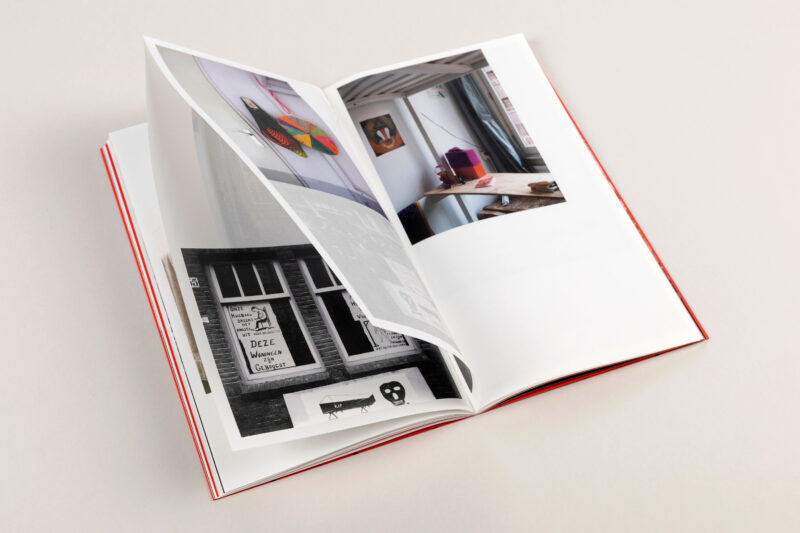

Short-lived optimism

My new home is in the Staatsliedenbuurt district of Amsterdam and, as it turns out, it’s a part of town brimming with frustration about the housing shortage. The apartment is located in a state monument designed in 1918 by H.P. Berlage and J.C. van Epen in the rationalist style. It is an example of a large-scale workers’ housing complex from the early twentieth century, made possible by the then new Housing Act.

The optimism of the early twentieth century is reflected in the bright interiors, the bay windows and the use of decorative brickwork. This optimism proved short-lived, however, because by 1932 the tenants were refusing to pay rent until their demands for lower rents and better maintenance were met. Their strike was eventually ended with an iron fist.

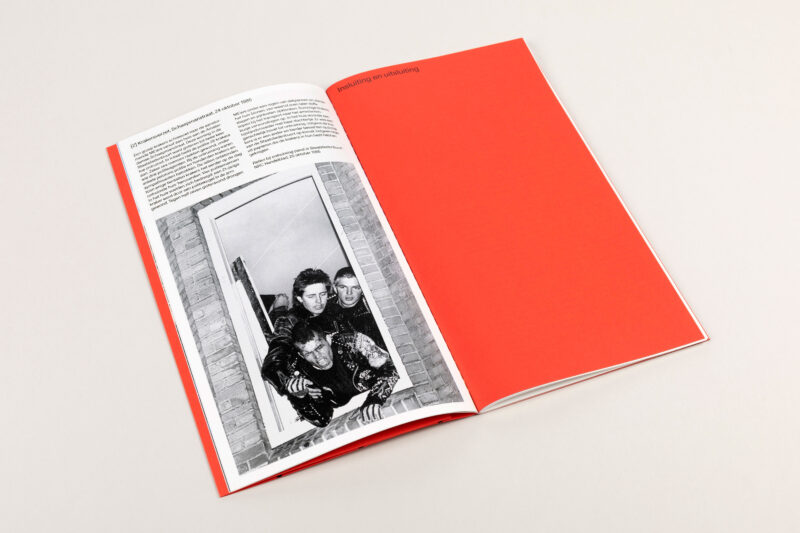

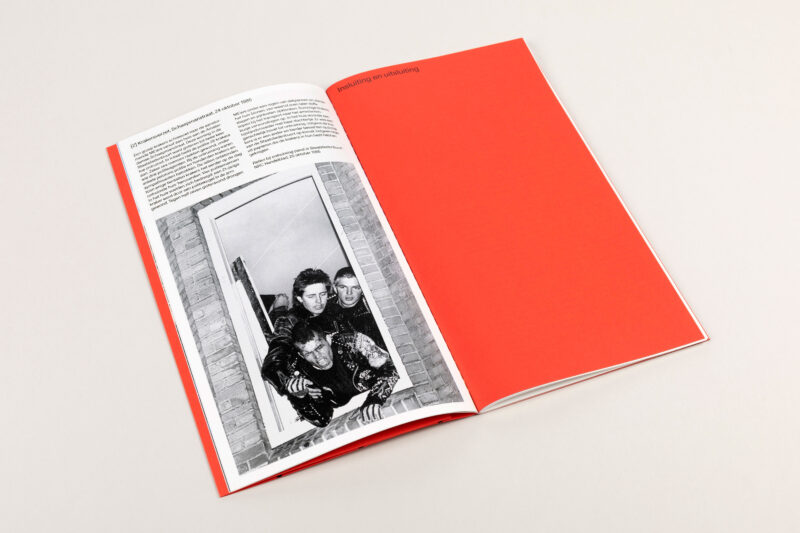

But things got worse in 1985. The Staatsliedenbuurt was taken over by squatters who opposed the housing shortage, the level of vacancy and the law that banned squatting. The eviction of squatters from a neighbouring building in the same block as Berlage and Van Epen ended in a battle in which shots were even fired. The low point came when squatter Hans Kok died in a police cell on the night of the eviction.

These are historical events in a long and ongoing collective struggle for better housing rights in Amsterdam and the Netherlands that took place in and around my new neighbourhood. For me, the bedsprings placed in front of windows to barricade squatted buildings on the streetscapes of the 1980s and early 1990s visually symbolize the squatter movement. The right to housing, and hence the right to a bed, was safeguarded by using that same bed to prevent eviction.

The move from the safe, soft, horizontal plane of the bed to the hard, aggressive, vertical plane of the window has always fascinated me. The mesh in front of the windows on the Schaepmanstraat references that in a certain way, and later I used bedsprings in my work to illustrate this inversion from soft to hard, from lying to standing.

Inclusion and exclusion

For years my work has focused on inclusion and exclusion, and they form the core of my functioning in society and my social existence. The borderline between extremes intrigues me, and I focus specifically on the point where those two extremes meet. They are the objects and constructions that mark the transition from inside to outside, from safe to unsafe, from public to private, even from yes to no, and I employ them to provoke discussion. Visible and invisible walls, roofs, windows, doors, stairs, fences, borders and barriers should keep us safe, but they also prevent us from being free.

The first time I made a cage was for Rosa-Luxemburgplatz in Berlin. It was an aviary for birds. The letters that Luxemburg wrote from her prison cell in Wronke to Sophie Liebknecht provided the inspiration for Voliere (2007). Luxemburg refers in these letters to the birds she hears, and they remind her of their walks together in Tiergarten as an expression of her desire for freedom. I wanted to convey that, and the way to do it was through inversion: by depriving the birds of their freedom.

That same year I made inaccessibility and hierarchic connectors (2007) at Palais de Tokyo in Paris. As part of the installation I sawed an opening – a window – in one of the walls of the exhibition space to illustrate the relationship between the work and the surroundings. The opening in the wall functioned as a reality check, as it were, and forced the visitor to look from inside to outside.

For Schaepmanstraat – De Kempenaerstraat (2020), I elaborated on the principles of the cage in Berlin and the window in Paris by bringing them together while slightly altering the direction. In doing this, I had the work untitled (frei) (2019) in the back of my mind. This consists of a light box with, in red warning letters, the word frei, which expresses that unconditional freedom does not exist. The light box was also inspired by a personal detail: Frei is the name of my son. Red does not signal a warning here of course but is a loving light.

With Schaepmanstraat – De Kempenaerstraat (2020) I covered the windows of my corner flat with panels of red steel mesh for a period of five months, thereby transforming my home into a cage. Although the intervention was designed to be seen from the outside, the finest outcome was that I was genuinely confined inside. A Covid infection meant that I had to spend a number of weeks in quarantine, so the cage for the world outside also became a cage for me inside.

This was a stifling experience that also evoked a sense of freedom. Stifling because the visible cage intensified my compulsory confinement. But it also felt safe because I genuinely experienced a sense of security ensconced in my own world. I created Schaepmanstraat – De Kempenaerstraat to be seen by countless passers-by. Yet circumstances meant that I became the main spectator, and the only person to perceive the work exactly in this way.

This architectural intervention touches on many aspects of my practice. It illuminates the heightened contrast between inside and outside, between public and private, between participating and being excluded. It also pushes the limits of the autonomy of an artwork and the semi-functionality of my work in public space.

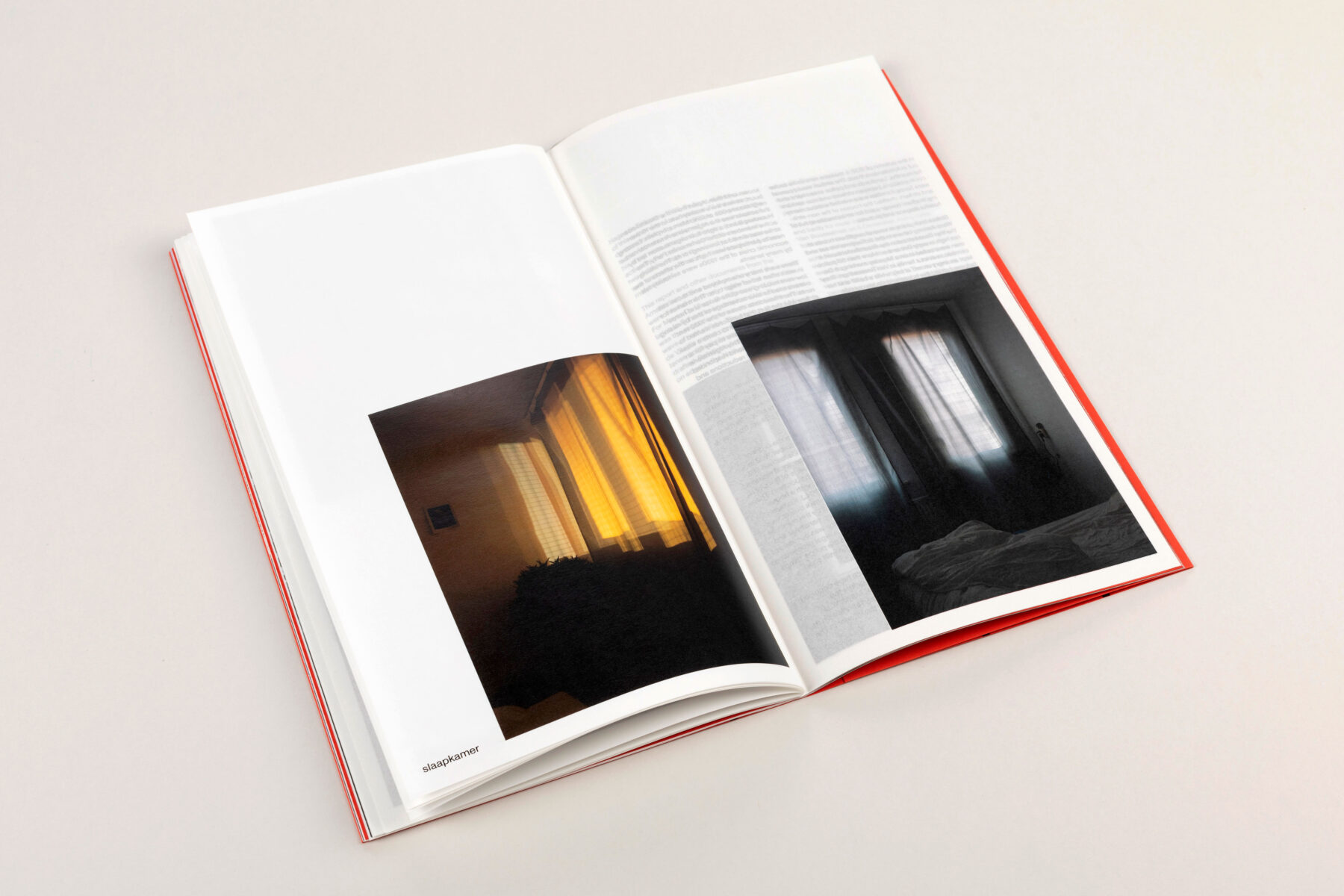

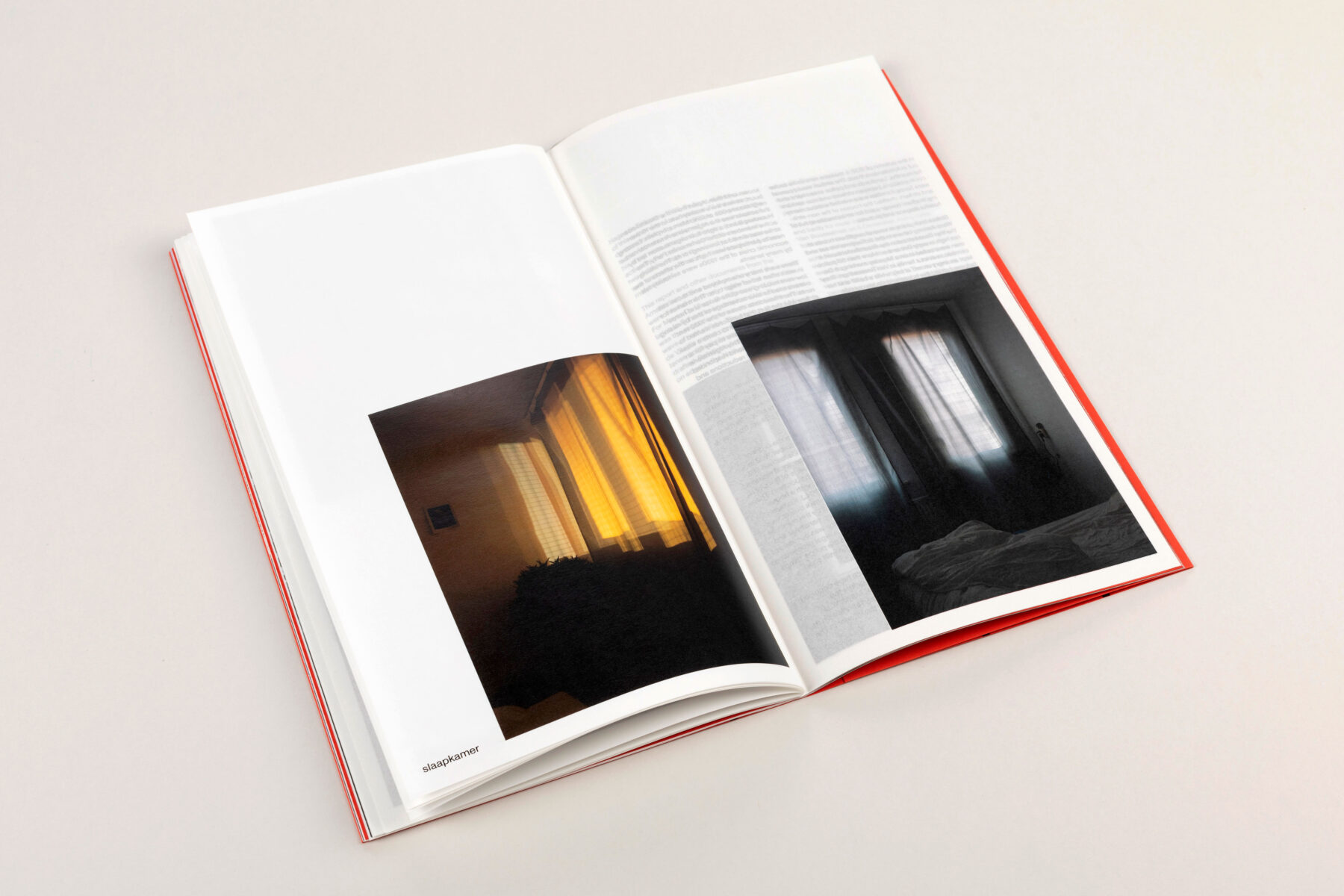

Inner life

The true experience that resulted from my forced confinement touches on very different subjects. In his Harvard GSD lecture in 2016, the American sociologist Richard Sennett talks about the relationship between ‘interiors’ and ‘interiority’. He explains the relationship between ‘inside’ and ‘subjectivity’ on the basis of the historical development of the home, in which the division into rooms, each with a function of its own, and the separation of the home from public space, contribute to the development of privacy. And that leads to the possibility of reflecting and becoming aware of our inner life. In other words: being with yourself – and not with others – opens up space for emotional development.

Inside, we experience the protection of the built enclosure. At the same time, the home shapes how we think about the world and our place in it. We project our image of the world into how we arrange our home, and the home itself stimulates our curiosity and creativity. The things we surround ourselves with express who we are and we create an environment that enables us to be who we are.

The possibility of reflecting results not only from the layout of the spaces but also from the simple fact that those spaces are there. The presence of various rooms for various functions gives clarity to the activities that take place in the home while also enabling you to withdraw from the group and be with yourself. Home is where you sleep, cook, eat, wash, play, dance, make love, relax, read, laugh and invite friends and family; or you can do none of that and simply be there.

“I did not become someone different, That I did not want to be,” Gil Scott-Heron sings in the number I’m New Here, after a stint in prison. I had the same thought when I found myself in my so-called self-built prison. It was a positive conclusion that made me think all the more about the function of the home. Could it have been different? By moving into a new place, could I have become a different person? Can a home change the occupant?

Caged inner world

If you walk along the street and peer into people’s homes, what you see probably says something about the occupants, but it says nothing about you. If you look at the world outside from your own home, especially in the city, it can say something about you. When I lived in my caged interior and looked out through the lattice of the mesh placed in front of the windows, I was reminded of Hieronymus Rodler’s interpretation (1531) of Leon Battista Alberti’s explanation of perspective and the ‘window’ to the world. I could see the world in perspective because I was isolated. The uneventful distance to life on the street and the rational division of the view into the squares of the mesh clarified my view and directed it inwards.

The right to housing is something natural that seems to have become a favour today, even though it is a basic human need. My experience, embedded and fed by the history of housing, and in part by my personal history, has in many ways coincided with the historical struggle and intersects with the theme of inclusion and exclusion that I have been exploring for so long in my work. Schaepmanstraat – De Kempenaerstraat has therefore become a spatial intervention that touches on both the past and the future.