Tools for rescue / Tools for hiding

2006

1050 x 1470 x 450 cm

window, yellow light, modular floor,

aluminium, epoxy, water, acrylic paint

on wooden panels, framed photograph

Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin

photo: Luuk Kramer

2006

1050 x 1470 x 450 cm

window, yellow light, modular floor,

aluminium, epoxy, water, acrylic paint

on wooden panels, framed photograph

Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin

photo: Luuk Kramer

Harald Fricke

Take a Seat in the Security Zone

On Lucas Lenglet’s Installations

He was a master of disaster. Hardly any other artist devoted himself as obsessively to depicting war and violence as Francisco Goya did. Maimed bodies, firing squads, mass panic – it almost seems as if Goya’s oeuvre were based on an apocalyptic vision of life on earth. The intent and means in his works are thereby deeply ambivalent. In his Desastres series, he repeatedly uses captions and titles to underscore that he is depicting real events seen with his own eyes; most of his paintings captivate with their conscious dramatization. No bloodthirsty detail is left out; light is often used for chiaroscuro contrasts like a spotlight illuminating the happenings. It is no coincidence that – most recently on the occasion of the retrospective in Berlin – Goya has been compared to a film director who consciously stages horror for emotional effects, leaving the viewer little room to take his distance.

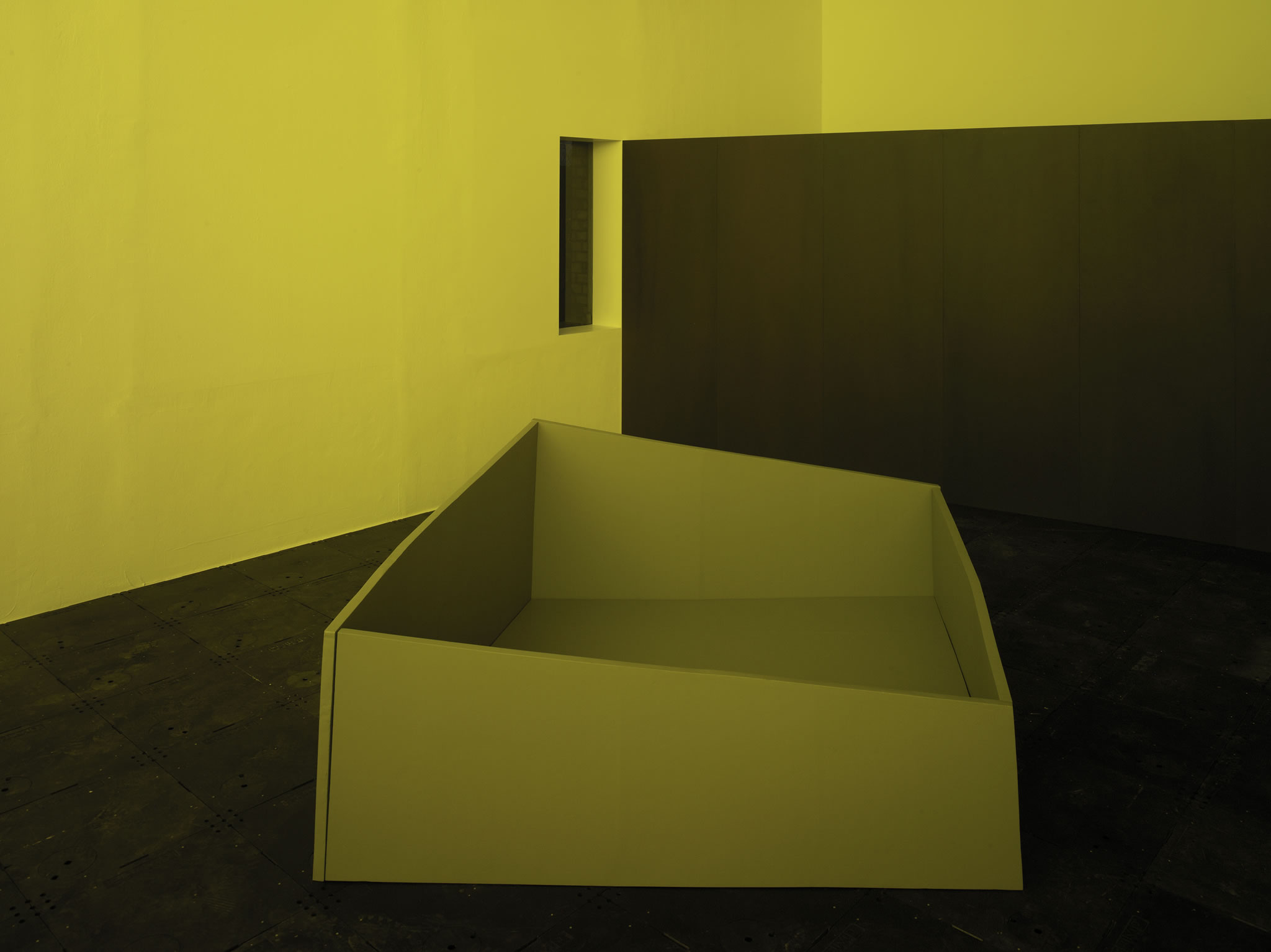

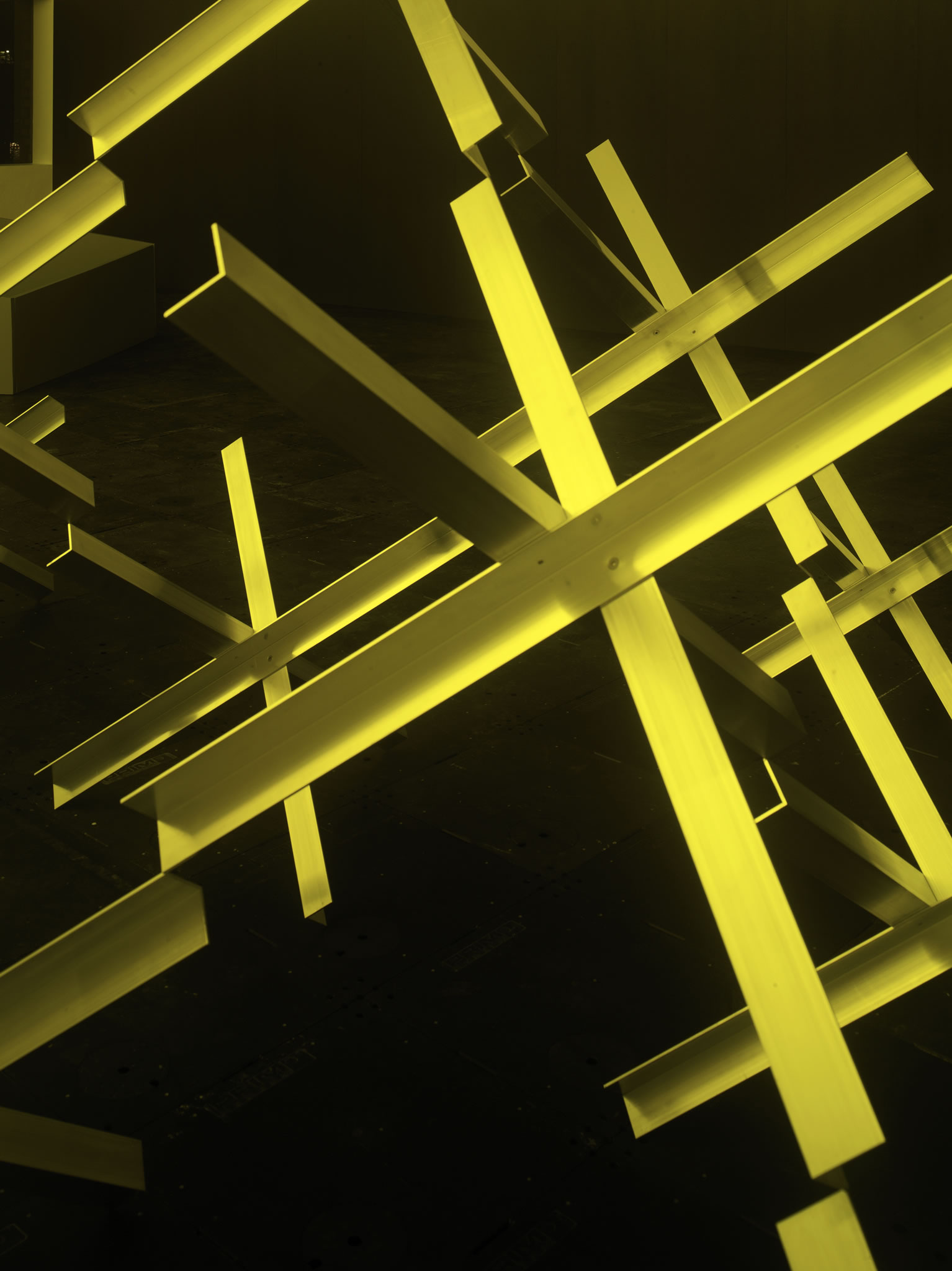

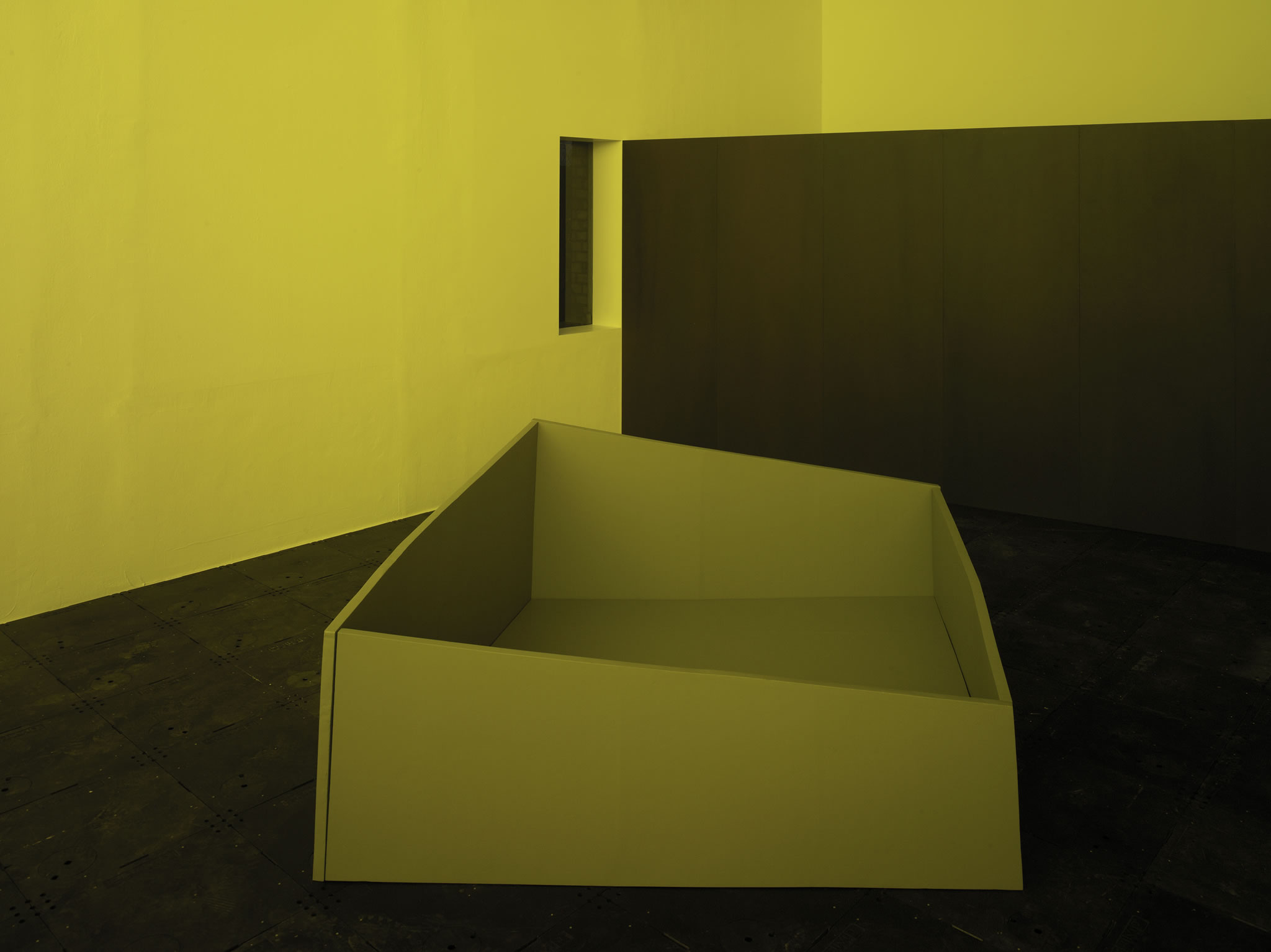

For his exhibition Tools For Rescue / Tools For Hiding in Künstlerhaus Bethanien, (1) one of the things the Dutch artist Lucas Lenglet has done is to reconstruct, as part of a traversible installation, an excerpt from Goya’s nocturnal The Fire in the night, painted in 1793/94. It is a commentary, not a realistic replica: where the original shows a frightened crowd of people hurriedly crawling over each other in flight from a glowing-hot blaze, Lenglet has instead created a module of epoxy resin, painted gray, that corresponds proportionally to the visual space the figures occupy. For Lenglet, the box-like object represents a sheltered terrain on which, as he says, the fleeing people from Goya’s painting could find refuge. At the same time, it is a multiple translation: the picture is transformed into a minimalist sculpture, while the picture’s object is marked as an abstract void. But above all, Lenglet updates the historical context: the sheltered zone is a metaphor for present-day conflicts, to which belong refugee camps, militarily secured enclaves, off-limits zones, and corridors to the daily reporting of the media.

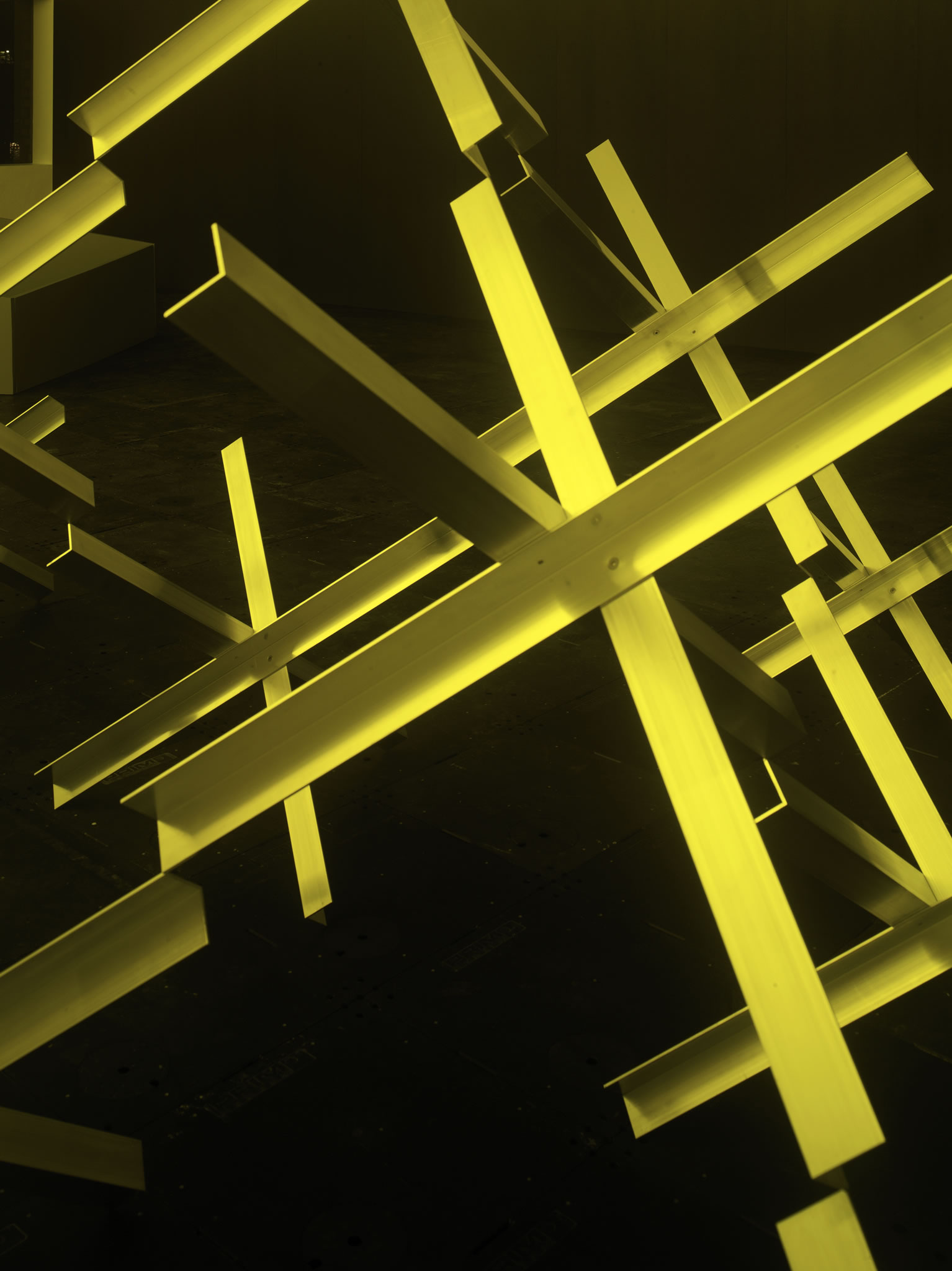

But it would be wrong to reduce Lenglet’s artistic production to a moral complaint or merely pacifist standpoint. Rather, he wants to show how the “technologies of power” (Michel Foucault), social behavior, and architecture mutually interpenetrate and change each other. This is why Tools for Rescue… confronts several model situations with each other, each of which points to the military approach to space. In addition to the epoxy body, there is an arrangement made of tank obstacles as well as an approximately 9-meter-long wall of 220-cm-high panels, painted brown, that lead to a photo. The photo, which Lenglet took in Zimbabwe, shows the passage through a fortress-like tower. All three formations correspond to a respectively specific “Safety Zone” with which inclusion or exclusion can be produced; the degree to which they could serve humanitarian or warlike purposes remains open.

Lenglet has already made (para-) military spatial arrangements the theme of several installations. For Vennsetcamostage, (2) a temporary architecture was designed using room dividers and the white camouflage nets of the Swedish army. Molotovspace (3) consisted of an area separated off with a pane of glass; at regular intervals, a Molotov cocktail was thrown in through a ceiling opening that the audience could not see, so that the otherwise empty space suddenly burned. In Vilnius, with Strategies of Honesty (4), Lenglet showed an extension of this setting; there, the fire was ignited on a cube, made of glass and steel elements, that moved on two rails. Lenglet summed up the installation, which blurred the boundary between artistic productivity and destructive act, in the formulation: “Are you a terrorist? No, just someone who believes very strongly in his ideas.”

In fact, Strategies of Honesty and Tools For Rescue… are directed against the over-hasty consensus between the viewer and the work of art. One enters a stage-like situation in which one’s own relationship to the exhibition room and to the exhibited objects is put into question. Since the sculptures of Minimal Art, at the latest, this “theatricality” (Michael Fried) provides the framework for “aesthetic subjectivity”, as art theoretician Juliane Rebentisch, for example, has described it. (5) If one considers that Lenglet places the structural connection between shelter, conflict, and violence in the center of his works, then it becomes clear that the viewer, too, is involved in a double game. He is the actor within a staging that deals with security measures with which – also as the consequence of political developments in times of a supposedly globally threatening terrorism – the society reacts to a usually only imaginary danger.

And so Lenglet calls his explorations an “archeology of action”, for which he constructs spaces as utopian sites for individual action. For here lies the difference from the art-historical model for Tools For Rescue…: Where Goya still directly addressed the viewer with the extremely drastic presentation of cruelty in order to arouse compassion, Lenglet consciously relinquishes the rhetoric of violence. Instead, he relies on interaction and participation – one is not deterred, but involved by the work of art. But the temptation does not lie in taking the viewer captive as in a labyrinth; Lenglet’s installations are better designated as “flights”. They are both: an attempt to escape conditions – and a constant accretion of these conditions. Rooms of flight and flights of rooms.

(1) Exhibition in Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin, Jan. 27-Feb. 1, 2006

(2) In the group exhibition Concrete, W139, Amsterdam, Feb. 9-March 10 2002

(3) In the group exhibition Cargo 3, Stichting Kunstwerk Loods 6, Amsterdam, June 1-2, 2002

(4) In the group exhibition Olandu Biuras / Dutch Bureau in the CAC, Vilnius; Nov. 19, 2004-Jan. 9, 2005

(5) Juliane Rebentisch, Ästhetik der Installation, Suhrkamp 2003; p. 280 ff.

Übersetzung ins Englische: Mitch Cohen (published in BE magazine)

———————————————————————————————————————————

The Object Quality of the Problem

Imagine: if for days the city was ruled by fear, it just so happens that fear turns into a sound, like a tinnitus drilling itself through a wall, just as the imagination did before, under siege, mindwandering through the city and through walls in an attempt to rationalise and seek opportunities for defense, attack and escape. But because the tinnitus never actually manages to get through, in a moment between awakening and dream, it may turn into the droning sounds of whatever swarm, giant or almost invisible, whose movements are unpredictable, chaotic but ruthless. The insurgent imagination likes to hallucinate rational chaos, counter-machines. Streets have become the corridors of a different nervous system, exterior turns into interior, fear expands the body into surreal yet lucid dimensions. What has happened?

If for a moment the city was a mental condition, it may elude as a whole into the next, evaporate, to quickly prove to be still there in the following moment, when a barricade turns against oneself, blocking one’s own movement or escape, when tools for protection turn into weapons, or, the shelter into a trap. Whose body, whose place, whose rights? Walls are membranes. What is left of the city, in all cases, are corridors, lines of flight. The corridors speak to each other, across centuries. Yet the appearance and disappearance of the city mirrors the appearance and disappearance of subjects, the threat of being identified as inferior and, consequently, of elimination, subjection to the naturalised violence of the enforced immune system. Or of an appearance elsewhere: the refugee who seeks and sometimes creates (often failing to do so) a place where the right to exist can actually materialise: home. Fear as the object quality of the problem: these are scenarios of situationist minimalism, producing the well-known unfamiliarity in the evidently familiar, the sensations and emotional traces of the dream. This is what is left after an act of uprooting and violent rewriting, after mobilisation with no return.

The spatial scenario that Lucas Lenglet has created is an answer to questions and events yet unknown. Or, if the event is known, its origins remain in the dark, but its otherness nevertheless appears in the form of the same, the already known, brutally pragmatic. In this spatial scenario, just as in the ruins of the Great Zimbabwe, the coordinates and possibilities to address of linear time are lost, entirely transformed into a stage-space of a ghostly all-presence, where defense and attack merge in pure expectation, the form and force of forces. We don’t know whether we face a model space of unforgotten scenarios of the past, a crime or disaster site, or a battlefield of the future, archaeology or prophecy. What remains is the scenario as a possibility, a possibility that already took place, now enclosed in amnesia: an unremembered past and an unimaginable future. All what is left is a set of possible tools. It may appear uncanny, since it is all about that what it is not: not terror nor anxiety, but cross-generic confusion – the disorientation of fear couples the hermetic form of apparition.

Force as the sacred background of violence: it takes place in formalisation itself, since it comes from somewhere else, from an origin that wants to remain mystical, unidentifiable, the very quality of which is to remain abstract. The formalisation of the appearance of force equals the abstraction of its origins, according to the formula that pure form appears as pure necessity. For force is the immediate abstraction, the possibility of violence to rule in latency, to enforce a rule, the law. It transforms the terrain into its stage. But any necessity, in order to be enforced, to take place, anticipates and creates the collateral. The collateral is not only in the destruction, but it is that what falls into the formless, into speechlessness. Its form is negative form.

Anselm Franke, January 2006

(written for the invitation of the exhibition Tools for rescue / Tools for hiding

at Künstlerhaus Bethanien Berlin)

———————————————————————————————————————————